Watson’s military service and wounds

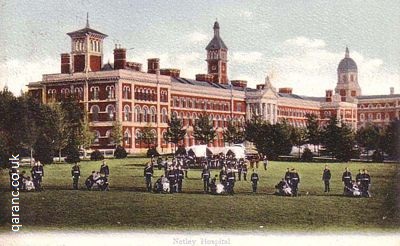

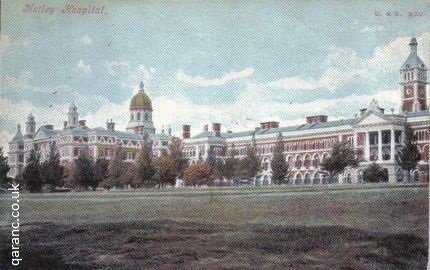

Feb. 29th, 2020 10:01 amIn the year 1878 I took my degree of Doctor of Medicine of the University of London, and proceeded to Netley to go through the course prescribed for surgeons in the army. (STUD)

Here are excerpts from Holmes and Watson by June Thomson. They give insights into Watson’s army days and contribute to building headcanons. I find dates especially helpful. For convenience, I compress the data given there for future reference:

(picture source 1 and 2)

Here are excerpts from Holmes and Watson by June Thomson. They give insights into Watson’s army days and contribute to building headcanons. I find dates especially helpful. For convenience, I compress the data given there for future reference:

At the end of his year’s service as house surgeon [at Bart’s], Watson was faced with a crucial decision about his future career: what should he do next? In order to set up in private practice, he needed capital which he did not possess.

He could remain in hospital service although this had its own disadvantages. Hospitals then employed only four consulting surgeons and, as a consequence, promotion was slow. Watson might have to wait until he was in his forties before a senior post became vacant.

To a medical man, a military career offered several advantages. An army assistant surgeon earned £200 a year, with his keep and living quarters provided. After ten years’ service, he could retire on half pay with enough money saved to set himself up in private practice.

Watson’s prep studies for the army:

The Army Medical School at Netley in Hampshire, later called the Royal Army Medical School, was first established at Fort Pitt, Chatham, in 1860 and was moved to Netley three years later when the military hospital, the Royal Victoria, was opened. One of the wards was converted into a classroom while laboratories as well as quarters and mess facilities for the students were housed in separate buildings behind the main hospital block.

(picture source 1 and 2)

There were two courses a year at Netley, each lasting five months, the first beginning in April, the second in October.

The course, which was divided into two parts, covered such subjects as hygiene, including the burial of the dead, as well as military surgery and pathology. Field exercises were also organized during which the candidates were expected to choose suitable sites for latrines, kitchens and dressing-stations.

During their time at Netley, the candidates were expected to obey army discipline, which included the wearing of uniform and attendance at parades. Their duties also entailed caring for patients in the wards.

In February 1880, if the suggested chronology is correct, he became Lieutenant John H. Watson, a rank he never referred to after he returned to civilian life. Assuming he embarked [to India] in March 1880, he arrived in Bombay in April, after a sea voyage lasting a month.

Watson’s probable route to Kandahar: after travelling from Bombay to Karachi by steamer, he then went by rail to Sibi and from there by horse and camel caravan across the mountains to Kandahar, encamping at night.

In the meantime, the war had been gathering momentum. The two forces met at the village of Maiwand, fifty miles to the north-west of Kandahar, in the early morning of 27th July 1880 on a hot, dusty plain dissected by dry water courses. Watson was later to speak of seeing his comrades “hacked to pieces at Maiwand” (STUD), a possible reference to the gallant rearguard action which was fought by the survivors of two companies of the 66th who stood back to back, fighting off the advancing tribesmen until all were killed.

Watson’s injuries:

• a bullet in his left shoulder fired from a jezail rifle, one of the Afghan long-barrelled guns, which shattered the bone, presumably his collar-bone, and grazed the subclavian artery.

• a bullet that damaged his Achilles tendon (“whence come Toby, and a six-mile limp for a half-pay officer with a damaged tendo Achillis” SIGN).

In the face of the fierce onslaught, the defences broke and what remained of the British forces turned and fled, including the medical staff of a field hospital who abandoned their patients, leaving them lying on stretchers. The Afghans remained behind to loot the baggage and dismember all those found on the battlefield, both the living and the dead, assisted by their womenfolk.By the way, at one point, being fresh from the university and penniless, ACD considered joining the army himself but instead grasped the opportunity of earning some money as a ship’s doctor.

Casualties, Watson among them, were transferred to the base hospital at Peshawar, the capital of the British north-west Indian possessions. Here Watson began to recover until he contracted typhoid.

There is no doubt Watson was gravely ill but his statement that "for months my life was despaired of" is a little exaggerated. Typhoid fever usually lasts about five weeks and the time scale will not allow for a protracted illness. No doubt the weeks he suffered seemed like months to him. In fact, he was in the Peshawar hospital for less than two months for by the end of October he was back in Bombay.

He had to make the 1,600 mile journey south by train and boat in time to embark on the troopship SS Orontes which sailed from Bombay on 31st October 1880. Having left Bombay, she called at Malta on 16th November and finally arrived at Portsmouth on the afternoon of Friday 26th November, ‘bringing home the first troops from Afghanistan, including eighteen invalids.’

Watson’s state of mind: He was certainly bitter. His health, as he himself states, was 'irretrievably ruined’ and the prospects of beginning a new career in civilian life seemed bleak. Even his rugby-playing days were over. From the symptoms of which he was later to complain, including sleeplessness, depression, irritability and nervous tension, he was probably suffering from the effects of post-traumatic stress disorder, a condition for which today he would receive treatment.

When a man is in the very early twenties he will not be taken seriously as a practitioner, and though I looked old for my age, it was clear that I had to fill in my time in some other way. My plans were all exceedingly fluid, and I was ready to join the Army, Navy, Indian Service or anything which offered an opening. […] I suddenly received a telegram telling me to come to Liverpool and to take medical charge of the African Steam Navigation Company’s Mayumba, bound for the West Coast. In a week I was there, and on October 22, 1881, we started on our voyage. (Memories and Adventures)